Jack Kirby’s 95th Birthday :: On Story Endings and the Rapture of Art

Today is Jack Kirby’s 95th birthday. The blogosphere hums with well-deserved tributes to Kirby on this day, and I want to join in the celebration by chatting about a few issues of the Kirby and Stan Lee Fantastic Four run.

Last year, as part of the Hooded Utilitarian‘s International Best Comics Poll, I chose my ten favorite comics of all time, and Fantastic Four #62 (“…And One Shall Save Him!” May 1967) was the Kirby that made the cut. I still adore this comic, and you might remember it: it’s the one where Reed Richards is stranded in the Negative Zone, drifting towards an explosive death, until he is saved by Triton the Inhuman, who brings him back to our universe and the Baxter Building. (Unfortunately, Blastaar, a Negative Zone No-Good-Nick, follows them to our world, precipitating a battle that would take up all of FF #63.)

In my opinion, Kirby’s art was at its peak during this period. Beginning with FF #44 (November 1965), Kirby’s pencils were inked by Joe Sinnott, a collaborator who lavished attention on the superhuman amount of detail in Kirby’s art, and who softened the faces and bodies of Kirby’s characters, giving them an attractive Hal Foster-ish sheen. (To be fair, some fans think that Sinnott fiddled with Kirby’s art too much, and they prefer inker Mike Royer‘s absolute fidelity to Kirby’s pencils.) The Kirby-Sinnott Techno-Futurist Humanism tore up the pages of the FF for the next two years, ending only when Marvel, in a money saving move, told their artists to stop drawing on paper that was twice as big as the printed comic. Instead, Marvel dropped down to original art only 1.5 times the size of the printed page. In the FF, the switch occurs with #68 (November 1967), a painful comic for me to read: I see Kirby struggle with the limitations of his diminished canvas, and I don’t think his art was ever as transcendent again.  Again, though, many disagree with me. In his Eisner-winning book Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby (2011)–incidentally, a must-read for folks even tangentially interested in Kirby–my buddy Charles Hatfield argues that Kirby’s artistic zenith came with his DC Fourth World Comics (1970-73), even though DC had by then also adopted the 1.5 original art size. Luckily, nobody has to choose either the FF or the Fourth World; we can just read and re-read both–and the mountain of other sensational Kirby comics–for the rest of our lives.

Again, though, many disagree with me. In his Eisner-winning book Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby (2011)–incidentally, a must-read for folks even tangentially interested in Kirby–my buddy Charles Hatfield argues that Kirby’s artistic zenith came with his DC Fourth World Comics (1970-73), even though DC had by then also adopted the 1.5 original art size. Luckily, nobody has to choose either the FF or the Fourth World; we can just read and re-read both–and the mountain of other sensational Kirby comics–for the rest of our lives.

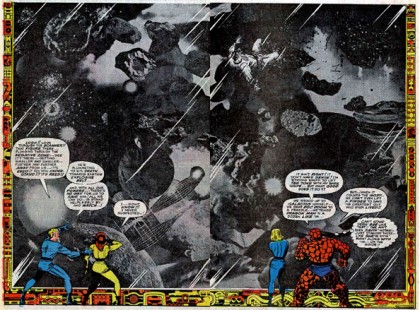

But back to FF #62. In retrospect, I think the reason FF #62 made my HU Top Ten is because that comic contains my all-time favorite Kirby image, a double-page collage/drawing of a massive video monitor in FF headquarters broadcasting Reed Richards’ plight in the Negative Zone, while the rest of the superteam watches helplessly.  If I chose my canonical Kirby today, though, I might change my mind. I might opt for FF #60 (March 1967) instead, because #60 is the one time when Kirby comes closest to sticking the ending of one of his comics. My use of the phrase “sticking the ending” implies that Kirby somehow messes up the conclusions of many of his stories, and, alas, I do think that’s a flaw in his work. As others before me have pointed out, too many of the FF plots–which over the course of the title were increasingly plotted by Kirby alone–ended with Reed Richards building or borrowing some arcane space-age device to defeat a menace and/or resolve narrative conflicts. Reed constructs a “jammer” to block the ray beaming power to the Super Skrull (#18, September 1963); Reed creates a machine that uses sound waves to evaporate the water in the helmets of the invading Atlantean fleet (Annual #1, September 1963); Reed assembles an intergalactic telephone to call the Infant Terrible’s parents (#24, March 1964); Reed’s “power-ray” restores the FF’s superpowers twice, once on the Skrull home planet (#37, April 1965) and once in the Baxter Building during a battle with Dr. Doom (#40, July 1965); Reed borrows a machine from the Watcher to banish an army of supervillains from his wedding to Sue Storm (Annual #3, August 1965); Reed threatens Galactus with the Ultimate Nullifier (#50, May 1966); Reed slams an explosion-dampening helmet down onto Blastaar’s head, rendering him powerless (#63, June 1967); and though I could list more, that’s enough. Too often, Lee and Kirby relied on a literal “Deus ex Machina,” a machine with the power of God, with the power to solve the Fantastic Four’s problems.

If I chose my canonical Kirby today, though, I might change my mind. I might opt for FF #60 (March 1967) instead, because #60 is the one time when Kirby comes closest to sticking the ending of one of his comics. My use of the phrase “sticking the ending” implies that Kirby somehow messes up the conclusions of many of his stories, and, alas, I do think that’s a flaw in his work. As others before me have pointed out, too many of the FF plots–which over the course of the title were increasingly plotted by Kirby alone–ended with Reed Richards building or borrowing some arcane space-age device to defeat a menace and/or resolve narrative conflicts. Reed constructs a “jammer” to block the ray beaming power to the Super Skrull (#18, September 1963); Reed creates a machine that uses sound waves to evaporate the water in the helmets of the invading Atlantean fleet (Annual #1, September 1963); Reed assembles an intergalactic telephone to call the Infant Terrible’s parents (#24, March 1964); Reed’s “power-ray” restores the FF’s superpowers twice, once on the Skrull home planet (#37, April 1965) and once in the Baxter Building during a battle with Dr. Doom (#40, July 1965); Reed borrows a machine from the Watcher to banish an army of supervillains from his wedding to Sue Storm (Annual #3, August 1965); Reed threatens Galactus with the Ultimate Nullifier (#50, May 1966); Reed slams an explosion-dampening helmet down onto Blastaar’s head, rendering him powerless (#63, June 1967); and though I could list more, that’s enough. Too often, Lee and Kirby relied on a literal “Deus ex Machina,” a machine with the power of God, with the power to solve the Fantastic Four’s problems.

Along with this Deus ex Machina repetition, I feel that Kirby’s visual storytelling would sometimes fail at the end of an issue. Kirby was legendarily overworked, and was from all accounts a swift and intuitive cartoonist: I picture him placing pencil to page without any thumbnailing, and drawing an issue in a single creative frenzy. It seems to me, though, that this improvisation got Kirby into trouble on the final page, where he’d suddenly realize his need to conclude the story in a quick, dramatic manner. The finales of FF issues are almost always crammed with more words and panels than the rest of the story, and important events on these last pages don’t get the visual-verbal care that they deserve. These final pages often end with a tier of three small panels, into which Stan Lee stuffs an overabundance of dialogue and a next issue blurb, and the result is that FF conclusions often feel cluttered and oddly paced. Here’s one particularly egregious example. Most of FF #35 (February 1965) is a standard adventure for the superpowered quartet, as a trip to State University (Reed’s alma mater) turns into a tussle with Diablo and Dragon Man. In the final panels of #35, however, Reed and Sue take a romantic stroll around State U., and Reed takes the opportunity to invoke a campus tradition and propose to Sue.  The proposal is the most important event in the issue–actually, it’s one of the most important events in FF history–but it’s a mix of tiny panels, muddy pictures and dense verbiage. The presence of the heart-tree leads Kirby to stage the final panel in a long shot that reduces Reed and Sue to blurry smudges, at a moment when we should feel closer to (and happy for) them, while Lee’s final caption is so prolix that it spills over into the previous panel. The whole sequence seems ham-fisted to me; the proposal deserves bigger panels, more panels, more emphasis imparted to it by Lee and Kirby.

The proposal is the most important event in the issue–actually, it’s one of the most important events in FF history–but it’s a mix of tiny panels, muddy pictures and dense verbiage. The presence of the heart-tree leads Kirby to stage the final panel in a long shot that reduces Reed and Sue to blurry smudges, at a moment when we should feel closer to (and happy for) them, while Lee’s final caption is so prolix that it spills over into the previous panel. The whole sequence seems ham-fisted to me; the proposal deserves bigger panels, more panels, more emphasis imparted to it by Lee and Kirby.

So how does FF #60 solve these problems and “stick the ending”? One reason is that the plot was planned out in advance from beginning to end–or at least it reads that way–and thus avoids the Deus ex Machina cliche. FF #60 is the conclusion of a four-issue epic where Dr. Doom steals the Silver Surfer’s power, and uses his new-found might to establish his rule over the nations of Earth and to attempt to destroy the FF. (In the four issues, there are a host of other subplots–most notably the Inhumans’ escape from a prison they’d been trapped in for eleven issues–but those aren’t relevant to #60’s slam-bang finish.) In #59 (February 1967), we see Reed build a “Flying Wing” designed to sap Doom’s cosmic energy–and you’re forgiven if you believe that this is just another Machina that’ll save the FF.  That’s not, however, the way the plot unfolds in FF #60. After much battling, during which the FF are hopelessly outmatched, Reed and the US Military attack Doom with a giant version of the Wing–and all it does is momentarily stun Doom. It doesn’t defeat him, and on the last page of the comic, Doom expresses his intent to reduce the Wing “to total nothingness.” Here’s the entire final page (from the reprint in Essential Fantastic Four Volume 3, hence the absence of color).

That’s not, however, the way the plot unfolds in FF #60. After much battling, during which the FF are hopelessly outmatched, Reed and the US Military attack Doom with a giant version of the Wing–and all it does is momentarily stun Doom. It doesn’t defeat him, and on the last page of the comic, Doom expresses his intent to reduce the Wing “to total nothingness.” Here’s the entire final page (from the reprint in Essential Fantastic Four Volume 3, hence the absence of color).  This page isn’t perfect; it has the final three-panel crammed tier symptomatic of other FF comics. (Whenever I teach Lee-Kirby in “Graphic Novel” classes, my decompressed-generation students always complain that these comics are “too wordy.”) The first time I read this story, however, I was relieved that the Flying Wing turned out to be (in the words of Reed Richards) a “decoy” to lure Doom into a more effective trap, the shield that Galactus placed around the Earth to keep the Silver Surfer prisoner. I love this ending because Lee and Kirby play fair with us: we readers could surmise that Galactus had “left behind some means of enforcing his edict”–it’s a logical extension of facts presented in previous FF issues–and the fact that Reed figured out this plan (and I didn’t) goes a long way towards defining him as a brilliant intellect. This ending both reinforces Reed’s character and deftly, ingeniously avoids the Deus ex Machina trap, and for those reasons FF #60 is at the top of my current Kirby canon.

This page isn’t perfect; it has the final three-panel crammed tier symptomatic of other FF comics. (Whenever I teach Lee-Kirby in “Graphic Novel” classes, my decompressed-generation students always complain that these comics are “too wordy.”) The first time I read this story, however, I was relieved that the Flying Wing turned out to be (in the words of Reed Richards) a “decoy” to lure Doom into a more effective trap, the shield that Galactus placed around the Earth to keep the Silver Surfer prisoner. I love this ending because Lee and Kirby play fair with us: we readers could surmise that Galactus had “left behind some means of enforcing his edict”–it’s a logical extension of facts presented in previous FF issues–and the fact that Reed figured out this plan (and I didn’t) goes a long way towards defining him as a brilliant intellect. This ending both reinforces Reed’s character and deftly, ingeniously avoids the Deus ex Machina trap, and for those reasons FF #60 is at the top of my current Kirby canon.

Reading over what I’ve written here, I’m worried that I’ve been too negative for a birthday tribute to the King. I’ve critiqued his improvisatory creative process and I’ve critiqued his dense, hurried endings, and at the heart of these critiques is a shift in my relationship with Kirby’s art. As a child, I loved Kirby’s stories, and I still like certain ones–like FF #60!–but I find most not-so-compelling nowadays. I’m more thrilled by Kirby’s graphic design and energetic drawing, like the detailing on the Flying Wing in the panel I reproduced from FF #59. It almost seems like comics fandom splits in two, with mainstream superhero fans worshipping Kirby for his world-building and soap-opera plotting, and alternative comics fans adoring the King for his vibrant mark-making and his connection to Pop Art. (Andrei Molotiu gave a terrific talk about Kirby, abstraction and Pop Art at the San Diego Comic Con this year.) So even though I nitpick about some aspects of Kirby’s art and storytelling, I’m able to find other aspects to appreciate and celebrate, because his work is accomplished, rich and multi-dimensional. He’s a Celestial, and our world is bigger because of him.

I think your objectivity is fair, and a fitting tribute. It’s far too easy to be a nostalgic sycophant where the King is concerned. But to be honest…I’ve been reading volume two of the Spidey Essentials and I’ve noticed those issues have a lot of those cramped endings, too. I dunno if I put it down to the artist, or to Stan. From a pure storytelling perspective, it makes sense to wind things down with longer shots and smaller panels, especially after really action packed episodes. But then Stan has to go huckster at the end and try to sell the next issue (that’s not a value judgement, it is what it is). Those next issue captions are almost always unnecssarily longwinded. Of course, we can put this down to the times. These guys were making this stuff up as they went along. It’s easy to lose sight of that when we critique it retroactively.

Anyway, great article, man. And happy birthday, Jack. Keep surfing those cosmic waves.

That’s a good point about the Spider-Man stories, Justin. I think last-page compression bothers me less in SPIDER-MAN because Ditko typically worked in smaller panels than Kirby did; there feels like less of a disconnect between the story and its conclusion.

“Making this stuff up as they went along”: Absolutely right.

Craig, I love your piece and Justin’s comments. I do think that the little panels and prolix endings are more to the credit or blame of Stan Lee. I think that you find it in other artist’s that he worked with, Don Heck and Dick Ayers. I think there is a transition to more continued stories and larger panels in Lee’s work with Colan, Romita and John Buscema. This is connected with non Ditko artists working with larger panels and the continuation of stories. The flaw you pointed out to is found mostly in stories that conclude or are done in one. I actually read much of this great run when it first came out and I do find most comic writers of the silver age a bit too wordy. On Kirby’s achievement, I am split between the 50s CHALLENGERS, 60’s FF and THOR ( yes, with the dreaded VC) and the 70s DC FOURTH WORLD. Favorite issue is FF 51, “This Man, This Monster.” Yes a rare done in one and a story that has never been retroconned into a larger narrative and the unnamed protagonist was not made into Doctor DooM’s second cousin.

It is incredible that Kirby, Tardi and Crumb all have birthdays within a day or two of each other. Maybe there is something to be said for Astrology.

Great work Craig even though FF77 is the greatest comic of all time. This is fact not opinion. If I weren’t such a mature adult reader, I would point out that Psycho-Man could rip Blastaar to shreds, bit I am, so I won’t.

(Whenever I teach Lee-Kirby in “Graphic Novel” classes, my decompressed-generation students always complain that these comics are “too wordy.”)

I don’t think it’s just that the comics are too wordy, it’s that Stan Lee narrates the thing happening in the panel too often. I recently read Marvel Masterworks Hulk and I didn’t find a narration box that said something that wasn’t happening in the panel. It gets really annoying.